Photo by Jonathan Weiss on Unsplash

Photo by Jonathan Weiss on Unsplash

I am very lucky with my Department at my current high school and have to thank the wonderful Bobby Sullivan for providing a book study for our group. We are reading Enacting the Work of Language Instruction: High-Leverage Teaching Practices by Eileen Glissan and Richard Donato. For the most part, this book is meant for a newer teacher who does not necessarily use the TL in class all the time, but there is still plenty to be learned for the somewhat seasoned Proficiency-based teacher.

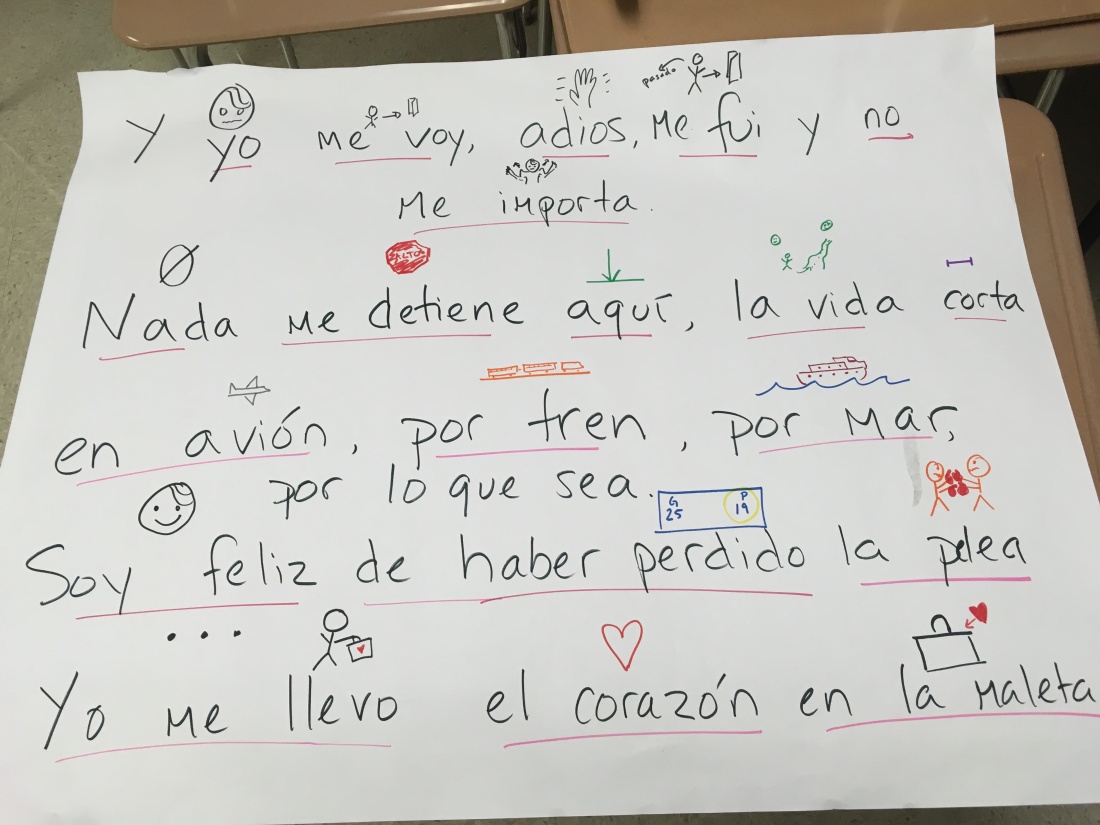

The first chapter set me to a new-to-me challenge: Teaching Vocabulary in Discourse. At first I was a bit skeptical, because the book suggests creating a thematic discourse, rather than treating words with isolated definitions, and the example is a house and house vocabulary. My initial thought was that it was easy to create a discourse around an object. But when I sat to create a discourse for my current unit on immigration, it felt more natural than I expected.

After reading the chapter, my takeaway is that a discourse is different from how I currently teach vocab in one subtle, yet important way: there is a central theme that connects the words beyond just being from the same thematic unit or text.

In my case, I had used an article and images from Bruno Catalano’s sculpture series, Travelers as a hook for the unit. An image from the sculpture series serves as the cohesive idea throughout the discourse and provides a meaningful context. Someone, I cannot find who or where had posted an article about the sculptures on one of the many Facebook groups I am in. The visuals worked well to open up the conversation. They are quite striking as you can see in this video that I started with. I showed the video and started and stopped it with various questions. The article that had been posted was also good, though I should have cut it more. The author’s writing is very comprehensible. The translation in the article of the a critic explaining the artwork was less so and my students struggled with it. Next time, I will cut the article and pre-teach some vocab so the article is less dense.

The article yielded a lot of good vocab and helped us to do some vocab generation. I decided to use this lesson as a practice for creating discourse. Below you can see my example. I am very happy with the idea of using discourses and though I do not think I have time to do that for every word that comes up, I love the idea of incorporating them into my regular vocabulary teaching. The characteristics and steps indicated with letters are on pages 33-34 of the book.

Proficiency target: Intermediate High by the end of the year

Topic: Immigration

6 thematic vocabulary words.

Factor

Motivos

Agridulce

Lanzarse

Exilio

Obra

Script (includes steps 4-8):

[projected image of one statue in Bruno Catalano’s Travelers]

J: OK, amigos, vamos a hablar de las estatuas, la obra, de Bruno Catalano y cómo él representa a muchos elementos de la inmigración y el inmigrante en su obra. En esta unidad, hablamos de los factores de la inmigración (g). Como dijimos, las caras de las figuras son cansadas y hasta tristes. Entonces, ¿por qué? ¿Cuáles son algunos factores (slower speech, meaningful intonations), factores, o motivos (again with intonation) para inmigrar? Factores, motivos,y razones son sinónimos (inclusive arm gesture, writing on the board with = sign with these words) en este caso. Y razones y motivos son cognados. Por ejemplo, un factor, motivo, o razón para crear arte es para fomentar conversación sobre un tema. Con tu compañero, ¿cuáles son algunos factores, motivos, y razones para inmigrar?

SS: chatting.

J: Hola, hola

SS: Coca cola

J: OK, dime. ¿Cuáles son algunos posibles motivos, factores, y razones….?

SS: una guerra.

J: OK, “Un motivo…” meaningful pause

SS: Un motivo es guerra. (sic)

J: Muy bien. Exacto, un motivo posible es una guerra. ¿Cuáles otros factores contribuyen a la inmigración?

[solicits several more answers, repeating vocab words. Most likely one student will say “exilio” since they have seen it before.]

J: OK. Puño a 5. Puño, no entiendo las palabras motivos y factores, 5 entiendo perfectamente bien que significan.[scan room for fist to five.] (a) Muy bien, exilio. Hablamos de esta palabra el otro día. Y como vemos en las caras de las estatuas, las caras son tristes. Un posible factor puede ser el exilio, porque el exilio es una situación negativa. Es cuando te fuerzan [pushing gesture, makes gesture to push statue on screen] a salir de tu país [walking as if pushed, makes gesture as if pushing statue on screen]. Con tu compañero, ¿Que recuerdas? Que entiendes de la palabra exilio. En tus palabras, ¿Qué es el exilio? [pointing to word on board]

SS: [talking]

J: ¿Qué te pasa?

SS: Calabaza.

J: Vale. Dos voluntarios por favor. (teacher holds up two fingers and ticks them off as students respond. She holds them up until she gets both 2 responses she asked for.) Gracias, Miguel.

S: Creo que es cuando en política no es bueno y tu necesitas salir.

J: Exactamente. Perfecto. El exilio es cuando hay una situación política, y los que tienen el poder te fuerzan a dejar el país porque no los apoyas (supportive gesture with hands). Julian Assange está en el exilio. Hay muchos cubanos en exilio en Miami porque no están de acuerdo con los Castro. Gracias, Annie

S: Creo que también es muy triste porque no quieres salir.

J: Claro. Muy buena observación, Annie, gracias. Perfecto. Claro que es muy triste. Es una situación forzada. Puño a 5: entiendes o no “exilio” (a)

J: OK chicos, entonces, vamos a volver a las estatuas, a la obra de arte, y miramos esta vez la postura. Dijimos que las estatuas se lanzan, que es caminar con determinación hacia un lugar. OK amigos. Levántense. Vamos a lanzarnos por el aula. Cómo caminamos cuando nos lanzamos? Practica con tu compañero.

SS: [students get up and start walking around room. Some with more enthusiasm than others.]

J: Hola, hola

SS: Coca cola.

J: OK, dos voluntarios por fa. Sí, Alex. {student shows lanzarse walk} Muy bien. Alex se lanza. Muy bien. Un aplauso. OK, otro voluntario. Gracias, Meghana. [student demonstrates walk]. Perfecto, Gracias. Meghana se lanza. OK, Puno a 5 para “lanzarse”. [holds up fist and 5 fingers, scans room.] (a) Pueden sentarse. OK. Perfecto. Amigos, para terminar con este repaso de vocabulario, miramos el vacío en los troncos de las estatuas, la obra. Dijimos que representaba varias cosas, que por ejemplo, cuando te mudas, siempre dejas una parte de ti en tu país natal. Y usamos la palabra agridulce. Agridulce es una palabra que representa lo negativo y positivo. Agri= negativo [underline agri in color, and dulce in another] dulce = positivo. En el caso de la inmigración, puede ser agridulce. Por un lado hay factores positivos, y por otro lado, hay factores negativos. Crea una lista con tu compañero. Cuales son las emociones positivas y cuales son los sentimientos negativos cuando una person inmigra.

SS: talking

J: [makes a two column chart with a plus and a negative at the top and agri over the negative sign and dulce over the positive sign.] Que te pasa

SS: Calabaza.

J: OK voluntarios, por fa. [writing on board as students share. Gets at least 3 ideas for each column.] Perfecto. Agri: triste, cansado, enojado. Dulce: emoción, anticipación, esperanza. Tu sientes todos estos sentimientos al mismo tiempo y es agri y dulce; agridulce. Con tu compañero, ¿Cuales son algunas cosas agridulces en tu vida?

SS: chatting.

J: OK 3 personas que no han hablado hoy. [holds up 3 fingers, ticking off as kids share]. Vale, Icaro.

S: la escuela [kids laugh].

J: OK. muy bien. Explica.

SS: Es mucho trabajo, pero estoy con mis amigos y también me gusta mucho jugar a fútbol, y aprendo mucha información.

J: Vale, perfecto. Ir a la escuela es agridulce, o por lo menos, hay ambivalencia. Dos personas más. Gracias, Jenny.

S: Películas pueden ser agridulces. Tristes y alegres.

J: Perfecto! Muy bien. OK, Miara.

SS: también, libros y canciones.

J: Excelente. ¿Puedes darme un ejemplo específico?

S: [names some pop song I do not know, but I nod knowingly along with other students] Con frecuencia el arte representa ideas agridulces como en el caso de las estatuas. Puño a cinco: agridulce (a). Un aplauso. OK. Chicos. Saquen el cuaderno. Con estas 5 palabras, escribe sobre el mensaje sobre la inmigración que Bruno Catalano comunica a través de su obra, su arte, su obra de arte, Los viajeros.